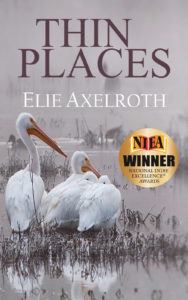

At the time of the winter solstice, the veil between heaven and earth narrows, opening us to the possibility of transformation. In some spiritual traditions, it’s called a thin place, an idea that captured my attention enough to use it as the title for my debut novel. Thin Places is the story of two people struggling with enormous loss —a young girl who’s been abandoned by her mother and a therapist who’s grieving the tragic death of her husband. Therapy is the thin place that transforms brokenness into healing.

At the time of the winter solstice, the veil between heaven and earth narrows, opening us to the possibility of transformation. In some spiritual traditions, it’s called a thin place, an idea that captured my attention enough to use it as the title for my debut novel. Thin Places is the story of two people struggling with enormous loss —a young girl who’s been abandoned by her mother and a therapist who’s grieving the tragic death of her husband. Therapy is the thin place that transforms brokenness into healing.

I’ve been witness to many thin places in my life—moments of opportunity, of joy, of a vision beyond myself. Sacred temples perched on a mountain top in Bhutan. Michelangelo’s David. Listening to Mary Oliver recite her poem, The Summer Day. The belly laugh of my children. The sweet and pungent taste of a slice of cherry pie.

The last six months, while recovering from a back injury, has surely not felt like an opportunity for transformation. In fact, I’ve experienced myself as standing outside of my life. As if I were experiencing not so much the pause of a sacred moment but the sharp-edged spidery crack of broken porcelain.

Along the way, I’ve deluded myself into believing that at some point, I would simply step back into my life. Everything from the past six months would be forgotten—and forgiven. Like those moving walkways in an airport—you can get on and off at any time. Luggage and all. No worries, because they always lead to the same gate at the end of the terminal.

In this spidery crack that is my life, I’ve had plenty of opportunity to contemplate what’s next—if what’s next is to be something different from the past.

Lately I’ve been trying my hand at sketching. I pack up my pad and pencils and take them with me on my neighborhood walk. I look for opportunities along the way to stop and draw. A bridge. Crows pecking at the grass. A jungle gym. A park bench. Sitting in a café with my coffee, I look around until I see what draws me in. I’m learning about perspective and angles and shading and plumb lines, simple concepts for now. I try to draw every line, every angle, but I’m intrigued by the idea that some lines are necessary while others are extraneous.

Lately I’ve been trying my hand at sketching. I pack up my pad and pencils and take them with me on my neighborhood walk. I look for opportunities along the way to stop and draw. A bridge. Crows pecking at the grass. A jungle gym. A park bench. Sitting in a café with my coffee, I look around until I see what draws me in. I’m learning about perspective and angles and shading and plumb lines, simple concepts for now. I try to draw every line, every angle, but I’m intrigued by the idea that some lines are necessary while others are extraneous.

I’ve discovered that it takes focused attention and concentration to see what’s really there. It is our brain that constructs—or reconstructs—what we perceive. But it is our eyes that really see. For instance, we divine a doorway from a line that disappears into the shadows. Shading suggests the depth of a planter box. Parallel lines of a sidewalk narrow into the distance. Our brains fill in the frame and the details.

It is an act of bravery and resistance to be willing to sit and stare long enough to take in what’s actually there. To draw and erase and redraw and stare some more. To see what’s real.

In these hours of concentrated focus, I feel a sense of contentment. My coffee is cold long before I’m ready to pack up my pencils. I’ve come to see that there’s no crack in my life. Unlike the airport walkway, we can’t get on and off when things get tough.

The best we can do is pray and rage and weep. And then gather up our senses and pay homage to what’s real. Because life continues, and along with the grief and loss and pain, there will also be moments of unexpected joy.

I invite you to read related posts Play it as it Lies and On Lost Sunglasses and the Meaning of Life. And my novel, Thin Places.